This is the last of a four-part series on how to live well in the age of overconsumption. Read the first article here, the second article here, and the third article here.

My favorite question is always: how can your home – the physical environment that carries the most meaning and over which you have the most control – play a part in your health and happiness? If the story of stuff tells us anything, it is that there is a powerful connection between people and their things, and we all have an opportunity to leverage it to our advantage. Let’s go back to Sandra Goldmark’s revelatory study of stuff. Goldmark observes that “through our decisions (and struggles) about stuff, we build our homes around ourselves. In doing so, we create a story for and of ourselves—an identity—within them.”

Similarly, the World Happiness Report stresses the role the built environment plays in health and happiness. Despite its emphasis on the development of trustworthy institutions and the ethos of a country, the World Happiness Report acknowledges that “many problems of mental and physical health can be prevented by better lifestyles (e.g., more exercise, better sleep, diet, social activities, volunteering, and mindfulness). We must also acknowledge that these lifestyle choices take place within social and physical environments – shaping these environments to make the “right” choice the easy choice is important, as we know that individual behavior change is difficult.”

But how do you know what you need? Evolution equipped us with some critical foundational urges and impulses. We instinctively seek food and water, shelter, social connections, tools, keepsakes, community, mates. Our ability to locate and fulfill these fundamental needs is hardwired into our brains and bodies, and a product of millions of years of survival. But we all live in a time when we have to make decisions about countless things for which evolution did not prepare us. Do you need that new sweater? What about a new rug or throw blanket? Is an upgrade to your iPhone and Apple Watch crucial right now? Is there a threshold at which point consumption becomes overconsumption? Not really.

Goldmark and Hinkel, among other scholars, say that our sense of appropriate consumption is dictated by those around us. None of us can step outside our existing communities, cultures, and systems of consumption entirely, but we can become more conscious of our consumption. We can mitigate the impacts of it, and ensure that whatever we do consume is healthier and more meaningful to us. The research tells us it is in our best interest to do so.

Chancellor and Lyumbomirsky, authors of the HAP model, include methods for getting off the hedonic treadmill. They point to the practice of gratitude, appreciation, and reminiscing as methods of finding joy in spending less. In terms of purchasing habits, they suggest using existing possessions in new ways (new software for an existing computer) and renting instead of buying (renting an outfit instead of purchasing) to prevent excess materialism. Much like the design of the built environment, people habituate more slowly to (and therefore take more pleasure out of) stimuli that vary; these strategies minimize boredom, help people learn new skills, and connect with others.

In a similar vein, happiness expert Gretchen Rubin writes extensively about the role of sensory experiences and mindfulness in creating a happier and more fulfilling life in her book Life in Five Senses: How Exploring the Senses Got Me Out of My Head and Into the World. She encourages people to tap into the physical world and to enjoy and pay attention to the physical, tactile experiences of moving through our environment. Goldhagen too, in Welcome To Your World, stresses the dangers of sensory-deprived spaces and reiterates the need to design a world with tactile materials, changing light conditions, and thermal and humidity temperature variations to engage people’s senses and positively impact their health.

Recall Bloom’s idea that people are essentialists–that origins matter. Bloom’s work is grounded in the “notion that there is more to the world than what strikes our senses. There is a deeper reality that has personal and moral significance.” Herein lies the connection between ritual and well-being. Locating, appreciating, and expressing the world beyond the sensory experience is a critical component of one’s well-being. Harvard Divinity scholar Casper Tu Kuile expands upon Bloom’s work and explores ritual as a means of connecting with ourselves, others, nature, and our uniquely human sense of the transcendent. He recommends creating daily, weekly, seasonal, and annual rituals to foster well-being, ranging from sacred reading and technology sabbaths to pilgrimages, celebrating the seasons, and creating community (think anything from book clubs to CrossFit gyms).

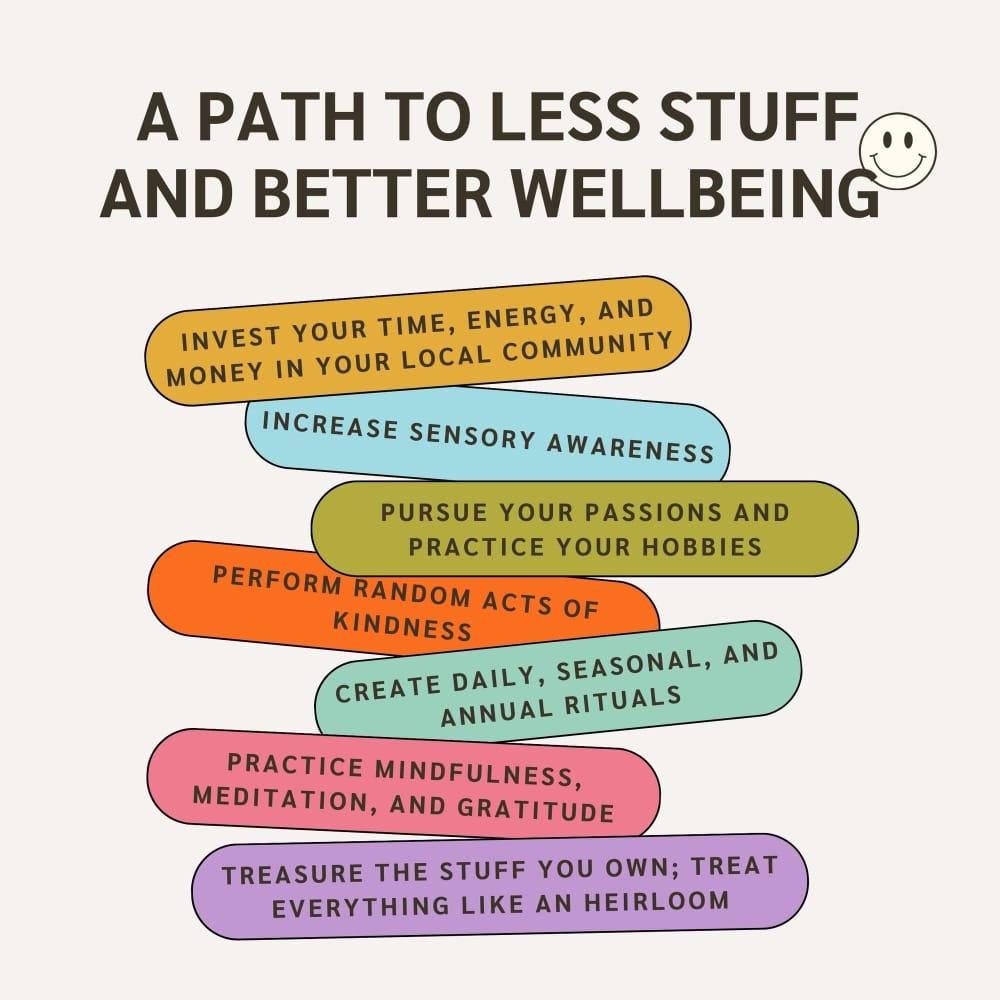

Goldmark, Antonovosky, Goldhagen, Chancellor and Lyumbomirsky, Hinkel, Bloom, Pinker, Rubin. All of these scholars have invaluable insights into what it means to live well. For all of us, as individuals, we can remember Sandra Goldmark’s words: “Have good stuff (not too much), mostly reclaimed. Care for it. Pass it on.” We can invest our time, energy, and money into our local communities, increase our sensory awareness, and practice our passions and hobbies. We go out of our way to perform random acts of kindness. We can create meaningful rituals, practice gratitude, and treasure what we already own.

All of these guidelines translate into design strategies for our homes. Home is the space in which so many activities play out, and we can create intentional spaces that will inspire actions day in and day out that support our well-being. Reinvesting in your local community may mean designing your home for gatherings. Increasing our sensory awareness becomes easier when our home is filled with natural, tactile, and healthy materials (think linen, cotton, plants, wood, cork, plaster, wool, jute, etc.). Practicing your hobbies and pursuing your passions is easier when you have dedicated, functional spaces in your home to do so. Performing random acts of kindness happens more often when you spend more time in your front yard, connecting and chatting with your neighbors, or when the design of your home makes it easy and convenient to get chores done (doing the dishes for your partner is a lot easier when you have a dishwasher and don’t have to handwash everything). For any ritual you’d like to embrace, own the objects that will enable it, whether that’s candles, favorite books, special kinds of tea, an espresso maker, or a cozy chair. Similarly, journaling and practicing yoga and meditation—all incredibly valuable for your health—depends largely on having a journal and a yoga mat.

Living well means embracing conscious consumption, and we all have an opportunity to do so in a way that improves the health of ourselves, those around the world manufacturing our goods, and the planet.

Find a vast network of vintage vendors and sustainable products in the Make Good Places Library and more best practices for a healthy home in the Make Good Places Guidelines.

Make Good Places

Make Good Places